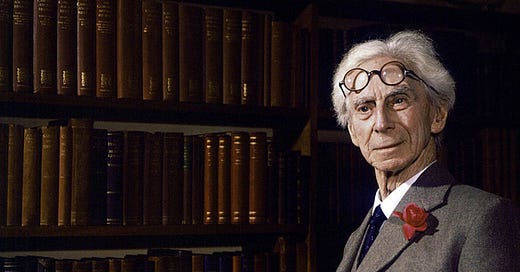

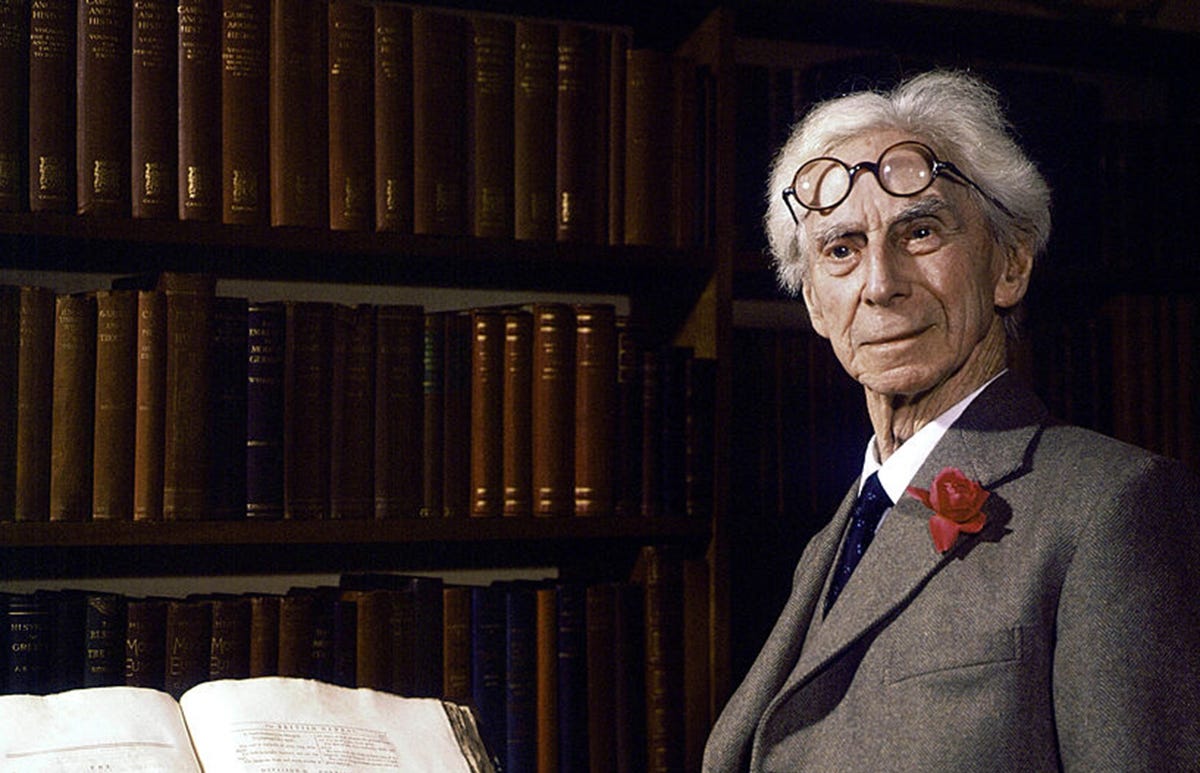

In the 20th century, there was probably no better example of the meeting place of philosophy and public life than Bertrand Russell. Paradoxically, however, it was Russell’s early brand of mathematical philosophy that set in motion a divorce of philosophy from its role in everyday life. What came to be thought of as ‘analytic’ philosophy is a view of the subject as a technical form of conceptual analysis, where academic professionals seek to define our common concepts and clarify through elimination of counterexamples, what we actually mean when when use a given word or idea. The process becomes rather dry, and the sheer cognitive horsepower in dreaming up a counterexample to every professed definition, becomes the measure of ‘good’ philosophy. Until Russell and his pupil Wittgenstein came along, however, philosophy was as much about ‘worldviews’ and the human being’s place in the cosmos, as it was a matter of knowledge, method and clarity.

Even though he was instrumental in this divorce, a purely technical view of philosophy was never Bertrand Russell’s original vision. To be sure, he did see the main duty of academic philosophy as clearing up conceptual messiness and a grounding of logic, maths and reasoning on a firm basis so that science could remain the benchmark of human knowledge.

However, Russell recognised that man cannot live on bread alone, and that there just are certain questions that we are by nature driven to ask, and which are unlikely to be answered by sheer scientific observation alone. Russell departed then from his ‘analytic’ progeny in recognising that metaphysical anxieties cannot simply be reduced to methodological mistakes. We really are concerned with life and death, with whether or not we are free, and whether our minds have any causal impact on the world of matter or are just passive receivers of the world of objects.

In his History of Western Philosophy, Russell says that philosophy has to occupy the middle ground between science and theology. Some questions, he concedes, don’t lend themselves to the scientific method for an answer, and yet, neither do these mysteries lend themselves to cosmological certainty of the type that you find in doctrinal theology. Russel writes:

‘Science tells us what we can know, but what we can know is little, and if we forget how much we cannot know we become insensitive to many things of great importance. Theology, on the other hand, induces a dogmatic belief that we have knowledge where in fact we have ignorance, and by doing so generates a kind of impertinent ignorance towards the universe. Uncertainty, in the presence of vivid hopes and fears, is painful, but must be endured if we wish to live without the support of comforting fairy tales. It is not good either to forget the questions that philosophy asks, or to persuade ourselves that we have found indubitable answers to them. To teach how to live without certainty, and yet without being paralysed by hesitation, is perhaps the chief thing that philosophy, in our age, can still do for those who study it.’

In an essay called Philosophy and Politics, Russell associates this delicate tentativeness with liberal politics. He says that such an approach to thinking can help cultivate a non-dogmatic approach to social problems, based on observation and testable and workable answers, as opposed to grand systematic utopias or ideologies derived from professed cosmological claims. For Russell, the key benefit of this brand of philosophical thinking is that it avoids the tendencies to certainty that breed totalitarianism. There are the totalitarians of the Platonic tradition, he says, whose world view is derived from a cosmic rationality about what a human being is and what his place in the world must be. There are also totalitarians of the Hegelian kind, who see human reality as a product of historical inevitability. Both these rationalistic totalitarianisms, Russell notes, believe answers to the big questions—and therefore answers to political problems—are a matters of discovering immutable laws. Once discovered, certainty is reached and the answers will be fixed, certain and commanding of authority. The advantage that the tentative liberal has is that he or she simply doesn’t buy the idea that such laws exist or that they can be discovered. Like the empirical scientist, the philosopher seeks to establish patterns based on observations, and thus we endeavour to make workable solutions based on these observations. However, also like a good scientist, we understand that our solutions can only ever be hypotheses based on contingent and limited human faculties, and as a result, subject to review. Russell notes:

‘The Liberal creed, in practice, is one of live-and-let-live, of toleration and freedom so far as public order permits, of moderation and absence of fanaticism in political programmes. Even democracy, when it becomes fanatical, as it did among Rousseau’s disciples in the French Revolution, ceases to be Liberal; indeed, a fanatical belief in democracy makes democratic institutions impossible…’

He goes on to say:

‘The essence of the Liberal outlook lies not in what opinions are held, but in how they are held: instead of being held dogmatically, they are held tentatively, with a consciousness that new evidence may at any moment lead to their abandonment.’

Crucially, for Russell, however, none of this means that we reject the possibility of an answer. The absence of a final knowledge of the absolute laws of the universe should not leave us in the equally dangerous form of certainty about the impossibility of knowledge, or epistemic nihilism or despair.

In another essay on the same themes, Philosophy for Laymen, Russell emphasises the necessity of a division between philosophy as an academic and technical discipline, and philosophy as a way of cultivating humility about knowledge. Once again, Russell repeats his view that philosophy helps everyone to cultivate the ability to live with uncertainty. He says:

‘To endure uncertainty is difficult, but so are most of the other virtues. For the learning of every virtue, there is an appropriate discipline, and the for the learning of suspended judgement the best discipline is philosophy.’

However, he says that there is a difference between tentativeness and humility about knowledge, and mere scepticism. Scepticism, for Russell, is not actually a virtue, because while seeming to be a kind of self-control about knowledge, it is really a form of disguised absolutism in itself. He writes:

‘Dogmatism and scepticism are both, in a sense, absolute philosophies; one is certain of knowing, the other of not knowing. What philosophy should dissipate is certainty, whether of knowledge or ignorance.’

This is a crucial point, because true philosophical thinking, as it relates to everyday life, is the art of living with the unknowns of existence, without falling into despair. It is a way of living meaningfully, retaining even a broad and sweeping view of the cosmos and our place within it, but without any of the narrowing and diminishing zealotry of religion. The implication of this view of philosophy, though not explored by Russell, is that each of us has a creative responsibility, not just morally, but metaphysically. We must all of us live as a sort of artist, balancing the known with the unknown, keeping alive the possibility of an answer without clinging to the solutions that we align with.

Despite the attractiveness of Russell’s insistence on a philosophy for everyday life, something is missing. He is still only really concerned with questions of method. The consolation of philosophy comes from the humility in knowledge generated by the big questions. What this leaves out is the very mystery at the heart of Being itself, irrespective of questions about the limitations of our knowledge. There just seems to be something essentially mysterious about who we are and the world we are thrown into, that transcend issues of knowledge.

In the best-selling novel Sophie’s World, Jostein Gaarder placed this mystery of Being at the heart of philosophy, highlighting it as the main reason we each of us need to become philosophers. Gaarder covers some of the same ground as Russell, in that questions of our knowledge and the need to rise above religious certainty are certainly recognised as the beginnings of philosophy.

The book starts with the main character Sophie getting a mysterious postcard with the question ‘Who are you?’ written on it. The question hits Sophie at just the right time, as a 14-year-old girl. She looks at herself in the mirror and experiences that sense of strangeness and familiarity we all recognise when we stop to spend time with our own reflection. She has a girl’s ambivalence about her looks, and reflects on the aspects of her self and body that she can choose, and the aspects of herself, like her looks, which seem imposed upon her. This blend of choice and imposition makes her realise that she doesn’t really know who she is. She begins to reflect on the strangeness of being alive, and remembers the way her grandmother had not really lived fully, before dying. In the intensity of approaching death, her grandmother had remarked on the richness of life. Sophie sees in death the tragedy and beauty of life’s shortness.

Another message comes for her, and it asks simply ‘where does the world come from?’ The simplicity of the question hides its intractability, just as the simplicity of the first hides the blend of familiarity and unfamiliarity we all experience about our own identities. If God created the world, who created God? If the world was not made by a creator, how can we make sense of the idea that something has always existed, that there is no starting point?

With these two questions Gaarder hits on the core premise of his book, which is that there are just some questions beyond the scope even of science, and that their intractability and the mystery they provoke in us, is part of their significance. Further correspondence comes from the author of these messages, Alberto Knox—her new tutor who has singled her out for an education in philosophy.

In the first letter, Alberto explains that the philosopher asks the kinds of questions she received in her first postcard because these point to a deeper need all human beings share—after the basic requirements of food and security have been satisfied. The realm of philosophy is the realm of a common human mystery, a mystery that undergirds a universal feature of who we are. Alberto adds that asking such questions is a necessary part of human life, that it is not a mere question of curiosity, but about participating in a quest that links us with the ages.

A lot of questions that puzzled people throughout time have been answered. Science dispelled a lot of the mysteries of human life, such as birth, the causes of disease, how the body works and what keeps the heavens turning. Nevertheless, there remain some major questions, for answers to which we can no longer appeal to authority. As science has answered many of the physical questions, it has robbed us of the external authority of God. Into this vacuum the philosopher steps. We are each of us now tasked with dealing with these questions on our own, but we do have the resources of the great thinkers to help us.

Alberto says:

‘Today… each individual has to discover his own answer to these same questions. You cannot find out whether there is a God or whether there is life after death by looking in an encyclopaedia. Nor does the encyclopaedia tell us how we ought to live. However, reading what other people have believed can help us formulate our own view of life.’

Three key illustrations convey the central message of the book in the introductory chapter. The first is the comparison of the very existence of the world to a white rabbit being pulled out of a magician’s hat. Behind the childlike simplicity of this image is the undeniable fact that no matter how sophisticated we are, no matter how many questions and problems our age of science and engineering seems to have solved, this is just how the world appears to us—an unfathomable and unsettling mystery. We can trace the causal sequences of many of life’s realities back only so far, eventually the mystery of Being itself never quite escapes the appearance of a magic trick. We are all, says Alberto, like insects on the tips of the rabbit’s fur, looking out into the mystery of life without a clear answer. However, many people retreat into the fur, they go back down into the darkness of the roots of the white rabbit’s hair. Except philosophers—they remain on the edges of the known and the unknown and relish the asking of the questions for their own sake.

Alberto goes on to ask Sophie what she would think if she was walking along a path in the woods and one day she stumbled on a spaceship and came face to face with a Martian. The point being that this is exactly the level of mystery and unsettling shock that we feel when we really see ourselves for who we are, in all our strangeness and mystery. A further thought experiment asks Sophie to imagine a family sitting around the breakfast table when suddenly the father starts flying and floats just below the ceiling. The mother turns around in fear and shock, while the baby boy at the table just adds this event to the many instances of daily wonder that he observes around him. The difference between the mother and child’s reaction is not in the strangeness of the father floating above the table, but in the difference in habituation between the child and mother. The mother has gotten used the world a certain way, while the child has no such expectations and operates with no fixed rules. The philosopher, says Alberto, tries to restore this exact state of perpetual wonder, where expectations don’t cloud our ability to see the mystery and strangeness of life. We might think that it is a violation of sensible norms that the father starts floating in space, but is such an event really all that different from the unlikeliness of Being itself? Alberto says:

‘Sadly, it is not only the force of gravity that we get used to as we grow up. The world itself becomes a habit in no time at all. It seems as if in the process of growing up we lose the ability to wonder about the world. And in doing so, we lose something central—something philosophers try to restore. For somewhere inside of ourselves, something tells us that life is a huge mystery. This is something that we once experienced, long before we learned to think the thought.’

This last sentence is important and deceptively simplistic-sounding. The experience of wonder is pre-conceptual. It is prior to the issues of method and critical thinking that Russell outlined as the core fruits of philosophy. The queerness of life is something that is not only a common feature of all human experience, it is something that is not reducible and solvable through rigorous analysis. It has to be confronted, integrated into our everyday lives, if we are not to descend into complacent and habitual thought. Alberto adds:

‘A philosopher never quite gets used the world. To him or her, the world continues to seem a bit unreasonable—bewildering, even enigmatic. Philosophers and small children thus have an important faculty in common. You might say that throughout his life a philosopher remains as thin-skinned as a child.’

In an age when doubt about scientific conclusions becomes a weapon of control, Russell’s insistence on the discipline of uncertainty has never been more relevant. Likewise, his distinction between philosophy as an academic discipline and philosophy as a way of cultivating intellectual virtue and combating fanaticism, is in need of revival. Philosophy has become too utilitarian. It is either self-help or it is arid concept-chopping. Its value as a tradition of character formation and a bulwark against the dual certainties of dogma and nihilistic scepticism is a constant. However, Jostein Gaarder’s insistence on the existential worth of what we might call ‘the philosophical imagination’ captures something over and above questions of method and epistemic restraint.

The fact of the matter is we live in an age when appeals to authority about what our lives mean and our place in the universe are just not viable. Even if we all decide to become Catholics and commit to a traditional worldview to ground all of our ethical commitments, these values no longer get their gravity and power from outside of us. Science may not be in direct conflict with an enchanted or religious world view, but it cannot co-exist with a view of the world that imposes itself from on high, or from outside. The role of human agency, even in a life of obeisance and Christian humility, is still paramount. The weight of our moral convictions comes from our level of commitment, not from our obedience to an outside law.

The good news is that we have a treasure house of traditions and centuries-old debates about what it means to be human and our place in the universe. Both Russell and Gaarder agree on that much. Against the presentism of much modern philosophy, the example of past thinkers acts as nourishment for our own independent thought, and helps us to confront the mystery of the human condition on our terms.

However, the mystery of human subjectivity, the very irreducibility and unfathomability of our own Being, can also act as some sort of common ground in securing something resembling a shared human worldview. There may be no one ideology that we can all share, or that comes to us imposed from without. However, there is a universalism and humanism to be found in the fact that who we are at the core is a profound mystery, one that reveals itself in awe and wonder, when we take time to contemplate and savour it.

References

Gaarder, J. (1994) Sophie’s World, London, Phoenix

Russell, B. (1957) History of Western Philosophy, London, George Allen and Unwin Ltd

Russell, B. (2009) Unpopular Essays, London, Routledge