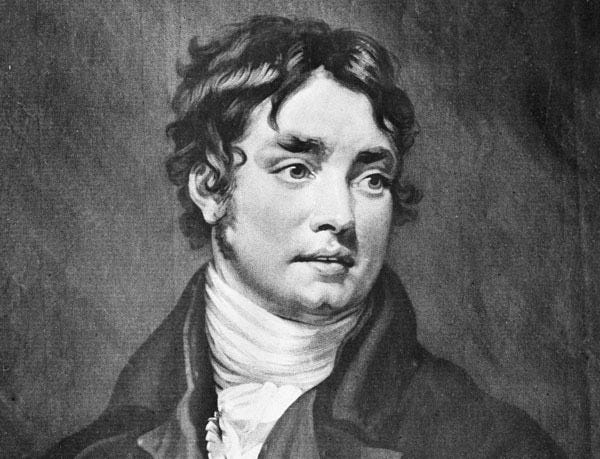

Well before cinema brought us the montage and Modernist poetry gave us the symphonic collage, Romanticism gave us the fragment. It was a form that was every bit as self-referential as the experiments in the twentieth century and every bit as much an emblem of the central concern of its time. Where the montage and the collage reflected the dissolution of old fixed forms of value and the way meaning is much bigger than the sum of its parts, the fragment embodied the core anxiety of post-Enlightenment Europe. That is, the recognition that in a scientifically knowable, material world, belonging and wholeness are impossible, and the simultaneous acknowledgement that while God may be dead, our need for him is not. The fragment, like the ruins of old abbeys and classical buildings, embodied the sense that while we may be broken and finite beings, we still long for the infinite, and there is some intimation of a larger unifying picture of reality in the partial and material perceptions of our everyday lives. Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Kubla Khan is just such a fragment, and his famous Preface to the poem claims that it is an unfinished account of a dream experienced in a laudanum-induced stupor. However, Coleridge’s structuring of the poem as a fragment is deliberate, and the poem is polished and precise in its effects. Coleridge’s use of this formal technique allows him to hint at a meaning beyond ordinary language and rational sense, indicating a reality just out of reach of our normal senses, but one intensely felt and apprehended through the poem’s impact on our nerves and bodies.

In the opening stanza, Coleridge uses a prickly, spritely diction and looping sentence structure, as well as a pouncing, ballad-like rhythm, to create his gothic effect. The famous opening line, so memorably used in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane, has become permanent in the cultural consciousness as much because of its cadence as its imagery. The nursery-rhyme feel and the folkloric incantations give the poem a timeless quality, as if we are hearing an ancient, anonymous song from a distant tradition. The short ‘i’ and ‘a’ sounds help to evoke the poems visionary exoticism, a place where human creation and dreadful nature co-exist. We can see this in ‘twice-five miles of fertile ground’, ‘girdled round’ and ‘bright, sinuous rills.’ The abrupt vowels here have a hypnotically jarring effect, making this opening description much more than a list of fantastic images. A few key images, however, do help to create the pagan and magical spirituality at the heart of the poem. In particular, ‘the sacred river’, the ‘incense-bearing tree’ and the ‘forest ancient as the hills.’ Perhaps the most important phrase in this stanza, and in the whole poem, is ‘caverns measureless to man.’ This embodies Coleridge’s idea of truth as something beyond rational perception, a deep, inner sense known only through feeling, in the hidden irrational recesses of our being and consciousness.

Into this fantasy of gothic imagery, however, Coleridge sketches a dark gorge, a rupture in the abundant greenery, from which a fountain spurts in a violent rage. In this stanza, not only is there a shift in imagery, the meter too is elongated and the rhymes are less balladic in their regularity. Alternating between couplets and schemes more akin to the sonnet, Coleridge tells of how the gorge is ‘slanted’ and ‘athwart’ the woody hill. This is a ‘savage place.’ At the same time it is ‘holy and enchanted,’ and ‘romantic.’ ‘Romantic’ for Coleridge would have meant other-worldly, synonymous with how we use ‘gothic’ to signify something exotic and beyond the normal. The narrative voice in this section is that of a parent telling his children a spooky story at bedtime. The scene is as holy ‘as e’er beneath the waning moon was haunted/By woman waiting for her demon lover.’ We are in the realm of folk ballads and ghost stories, but Coleridge is doing a lot more than just adapting the rhetoric for effect. He is communicating a spiritual truth by using popular language and imagery, a move that was revolutionary and perhaps even controversial in its time. The spirituality Coleridge is trying to communicate is his view of truth as a ‘water source’, a kind of fountain that rises from deep within us. The truth about who we are is ineffable. It is only faintly remembered. We experience a resonance between our inner life and the outer world, a sense of value and presence in moments of heightened experience. The truth and significance of these moments is real, but they are always outwith the grasp of rational knowledge. These fundamental truths can only be experienced through faltering, imaginative language and imagery.

The ‘sacred river’ is tossed up from the ‘dancing rocks,’ covering the surrounding country and flowing down to the ‘caverns measureless to man’ below Kubla’s pleasure dome. Here the use of alliteration and paradoxical image create a hypnotic disorientation, a kind of vertigo in the reader. This mirrors the vision-within-a-vision structure, through which Kubla himself hears ‘ancestral voices prophesying war.’ The lurch back into balladesque meter and rhyme help to conjure the dizzying, unsettling awakening arising from the din and glare of the landscape, which Coleridge continues to render in minute and precise description. This a dream-world, recognisable as a landscape, but one which makes little rational sense. Coleridge is placing us the reader, as well as the narrator and his subject Kubla, in a visionary state of mind. In doing so, the poet articulates something important about the human mind, its relation to nature and its creative powers. Here we can see the influence of the Romantic notion of the Sublime, in which rugged and imposing forms, such as high towering cliffs in a spooky landscape, unleash inner knowledge and imaginative possibilities. This is a state that is recognisable by its paradoxical sense of being both holy and terrifying, and it is a state through which we become something more—deeper beings and as a result more fully formed and creative persons.

In the final stanza, Coleridge shifts his imagery from a fantasy of landscape to a fantasy of human culture. It seems at first to be an incongruous move, a digression that breaks the unity of the poem. However, the change makes a strange sort of sense, precisely because the structure of the poem depends on this fragmented, vision-within-a-vision chain of inspirations discussed above. This time, the catalyst of the Sublime is not a violent spring or glimmering landscape, but a song played by ‘an Abyssinian maid’—the ‘damsel with a dulcimer.’ The opening lines of this stanza have the same fairytale, incantatory quality of the opening ones for the poem, but now Coleridge addresses us from a purely personal, interior place. Coleridge says that if he could ‘receive within me’ her ‘singing of Mount Abora’, he could:

‘…build that dome in air, That sunny dome! Those caves of ice!’

Following from his readings of German Idealism, in particular Kant and Schelling, Coleridge believed that we are not mere passive observers of nature, but integral participants in it. Where the philosophical scepticism of Descartes and David Hume led to a split between subject and object that could not be bridged, Coleridge followed the Idealists in thinking that there was a ground of intuitions that were preconditions of our perceptions, intuitions which cannot themselves be buttressed by logic or scientific certainty, but which we know in the intimacy of our inner consciousness. This is what Coleridge means by truth being a ‘water source.’ The ultimate truth of ourselves and our place in nature cannot be proved deductively, but it is known through an inner sense that swells up within us just like Coleridge’s rushing spring tossing up its shards of rock. At the root of who we are, then, is a mysticism, but it is a mysticism that provides a certainty much stronger than scientific argument. This is where the gothic language comes in. Such a fundamental mysticism can only be expressed in figurative language, a set of images and sounds which say the unsayable and communicate the simultaneous otherness and immediacy of human experience. This otherness of what is most basic to our experiences is embodied in the ‘damsel with a dulcimer.’ And yet, Coleridge himself is cut off from her, alienated from the primal truth she communicates in song. If only he could access it, he too could enjoy the primordial, creative power that makes all of us poets of existence. And yet he cannot. All he can muster is a fragment.

A central distinction in Coleridge’s thought is that between a mere allegory, and a symbol. This poem doesn’t ‘mean’ anything. An allegory is a poetic figure that ‘stands in’ for an object or an idea. A symbol, on the other hand, is a resonant image which makes some otherwise inarticulate truths communicable. It has no final meaning, but inspires in the reader constantly renewed interpretations and associations. It activates the imagination. To seek out allegories, is to seek to domesticate figurative language, to reduce it back down to the merely literal. All you are doing is translating one image into another. A symbol does not seek to translate but illuminate and inspire the reader to make their own connections and discover ever-greater significance in the poem being read. Kubla Khan is an expression of the power and depth of the human imagination. This is the faculty which Coleridge thought defines what it means to be human. It allows us to perceive unities, to make sense of our perceptions and shape them into a meaningful whole. It is a faculty which needs to be ignited, educated and refined, if we are to become fully human, and if nature itself is to reach its fullest consciousness. The fundamental mystery of the human mind and its relationship to the world, is not, for Coleridge, something which can be known or stated in literal statements. It takes a poem like Kubla Khan for this truth about the human condition to become fully alive within us.

Kubla Khan by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Or, a vision in a dream. A Fragment.

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately pleasure-dome decree: Where Alph, the sacred river, ran Through caverns measureless to man Down to a sunless sea. So twice five miles of fertile ground With walls and towers were girdled round; And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills, Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree; And here were forests ancient as the hills, Enfolding sunny spots of greenery. But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover! A savage place! as holy and enchanted As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted By woman wailing for her demon-lover! And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething, As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing, A mighty fountain momently was forced: Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail, Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail: And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever It flung up momently the sacred river. Five miles meandering with a mazy motion Through wood and dale the sacred river ran, Then reached the caverns measureless to man, And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean; And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far Ancestral voices prophesying war! The shadow of the dome of pleasure Floated midway on the waves; Where was heard the mingled measure From the fountain and the caves. It was a miracle of rare device, A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice! A damsel with a dulcimer In a vision once I saw: It was an Abyssinian maid And on her dulcimer she played, Singing of Mount Abora. Could I revive within me Her symphony and song, To such a deep delight ’twould win me, That with music loud and long, I would build that dome in air, That sunny dome! those caves of ice! And all who heard should see them there, And all should cry, Beware! Beware! His flashing eyes, his floating hair! Weave a circle round him thrice, And close your eyes with holy dread For he on honey-dew hath fed, And drunk the milk of Paradise.