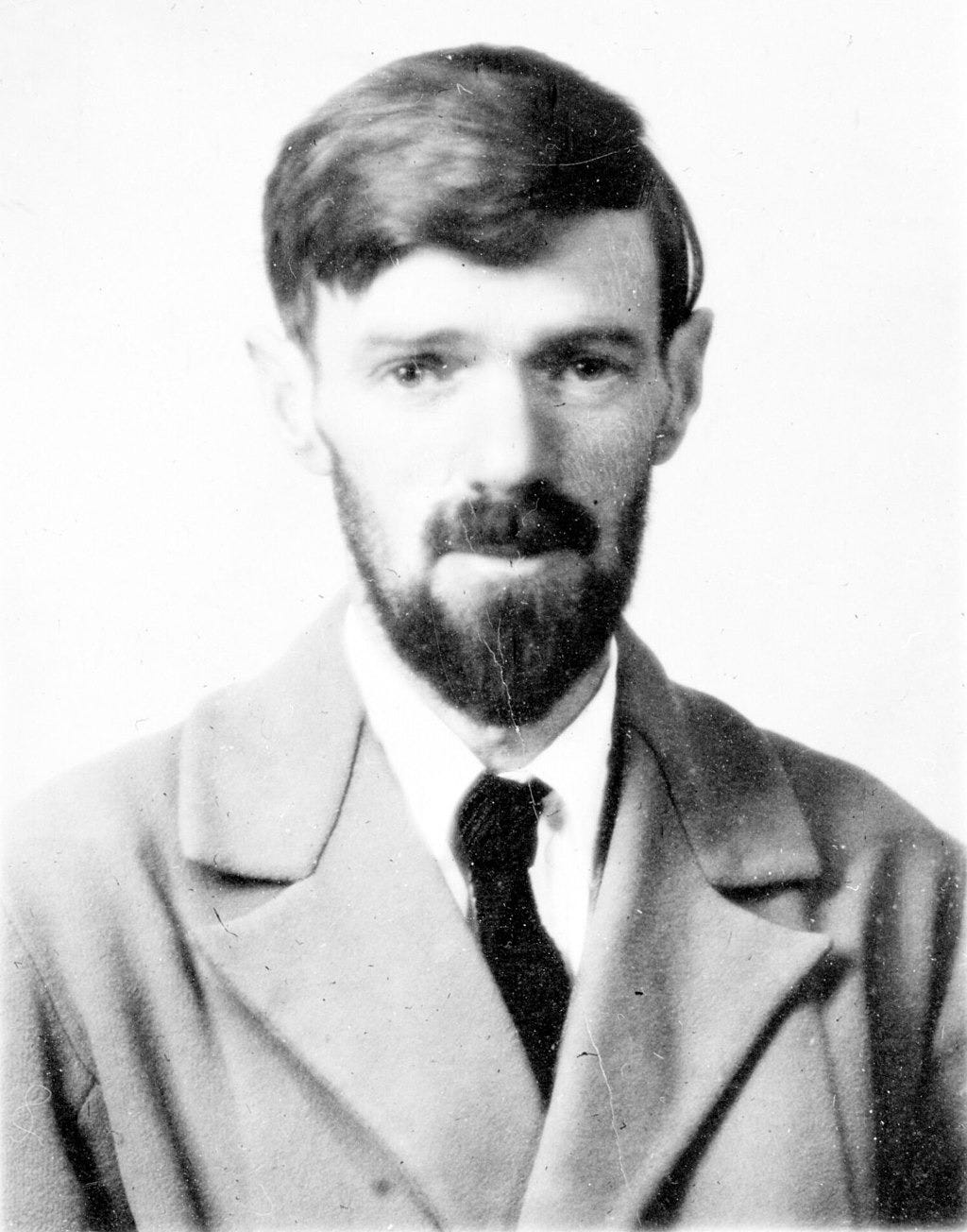

Becoming artists of ourselves: D.H. Lawrence affirms the mystery of death

Lawrence achieves the impossible by making death's mystery tangible and real

To T.S. Eliot, the body-centred spirituality of D.H. Lawrence was a brilliant and dangerous false prophesy. Lawrence famously pitted the heightened sensuality of bodily experience against the deadening effects of modern technology and industrial society. The antidote to the forces of mechanisation, for Lawrence, was a return to primal instinct. Eliot viewed this as a perfect example of the dangers of spiritual feeling divorced from the refining influence of religious custom and cultural tradition. In a series of lectures published as After Strange Gods (1934) Eliot said:

‘A man like Lawrence,… with his his acute sensibility, violent prejudices and passions, and lack of intellectual and social training, is admirably fitted to be an instrument for forces of of good or for forces of evil; or as we might expect, partly for one and partly for the other.’

Both Lawrence and Eliot would have agreed about one thing: that modernity is a kind of sickness. For Eliot, the sickness lay in the traumatic divorce from the past and its living traditions, and the resulting loss of wholeness, in society and in individuals, that this brought. For Lawrence, however, the sickness was a product of those very traditions and intellectual abstractions. They create, he thought, a neurotic conflict within us, between our forbidden desires and the dehumanising commands of corrupt, cultural authority. Both writers were raging against the contemporary malaise, but each saw the other’s antidote as exactly the problem. However, Eliot recognised that for all of Lawrence’s primitivism and worship of blood and instinct, he was a deeply spiritual writer. ‘The man’s vision is spiritual,’ wrote Eliot, ‘but spiritually sick.’

Lawrence’s friend Aldous Huxley was more understanding, though he had his own criticisms. In a broadcast interview given near the end of his life, Huxley spoke of Lawrence with qualified admiration. The same spirituality that Eliot had seen as sick, Huxley merely viewed as incomplete. Huxley said:

‘The blood and the flesh are there—and in certain respects they are wiser than the intellect. I mean if we interfere with the blood and the flesh with our conscious minds we get psychosomatic trouble. But on the other hand we have to do a lot of things with the conscious mind. I mean, why can’t we do both—we have to do both. This is the whole art of life: making the best of all worlds.’

For Lawrence, the darker forces of the human condition are not to be feared, but embraced and unleashed. They are to be fully confronted and accepted and even relished, rather than domesticated and fetishised. Lawrence was not advocating indulgence in violent and destructive habits, but rather he saw our dark, erotic and explosive impulses as the perfect cure for the constant control-freak diminishment of human creativity and the imagination. We must view his poem ‘Bavarian Gentians’ as an expression of this belief.

When it comes to his poetic style—though it has often been dismissed by scholars as a kind of arbitrary formlessness—for Lawrence, it was in fact a highly demanding discipline of expressionism. He saw his natural form as we might view the apparent chaos of a bird tossing and leaping on the channels of the wind. The movement seems random and without any power of will, when in fact it is a highly skilful movement that shifts and varies according to what is needed to maintain flight. Lawrence achieves success in this poem through principles that rise above mere form. The achievement is in his ability to harness the organic lyricism of his own voice. These lines may not have the rigour and control of traditional verse, but neither are they just random, unformed thoughts that don’t reach the end of the page. Lawrence stays true to an insistent, bardic and incantatory voice that wells up from within him, and his genius is in translating this unruly and turbulent music into something which makes sense to us, and which sticks in our minds forever.

Lawrence wrote this poem as we was dying. He sits in his weakening state contemplating the deep, almost neon and mystical glow of the petals on the gentian flower. He opens with a kind of swoon and rapture, the disorientation of a sick and dying man, but a man who is also experiencing a vague insight in his compromised state. ‘Not every man’ says Lawrence, can look on this flower in his own home, in ‘Soft September’ and in ‘Sad Michaelmas.’ The personal, subjective statement, coupled with the reference to the seasonal calendar, set the tone for the rest of the poem—a blend of private experience and prophetic declaration. Lawrence then goes on to riff on the colour and shape of the gentians, forms which evoke for him the mythic underworld of classical literature—‘Pluto’s gloom.’ This is a reference to the classical myth of Persephone, who was abducted while picking flowers, by the god of the underworld Pluto. She was eventually released but only for one part of the year, and thus giving birth to the seasons. Lawrence evokes this relationship between winter and spring, death and life, darkness and light, by the repetition of figures to describe the petals of the gentians. He repeats in slightly varied form, the idea that the flowers are like torches to light his way into the underworld and that they glow with a smoking darkness. For instance he first describes them as ‘big and dark’ and ‘torch-like with smoking blueness’ and then goes onto say they are ‘torch-like, with their blaze of darkness spread blue.’ And then still later says they are the ‘torch-flower of the smoking blue darkness.’ And from here he only doubles down on this conceit, with his slightly varied repetitions conveying the sense of a voice thinking allowed in bursts of incoherent, spontaneous thought. Except, the elegant and hymn-like rhythm shows us that these are not mere random scribbles, that Lawrence knows exactly the musical effect he wants to evoke. While the flowers are the light of ‘Pluto’s dark blue daze’, they are also as blue ‘as Demeter’s [Persephone’s mother and the goddess of grain] pale lamps give off light.’ In other words, the darkness and the light are entwined together, and this is the feeling Lawrence is reaching for in trying to describe the gentians. All of this so far seems like just imagistic utterance, without any real syntax to help us find our bearings. However, the first stanza ends with the imperative ‘lead me then, lead me the way.’ The commanding tone here is paradoxical, because he is asking to be led into the darkness, into the underworld of death. When this final verb ‘lead’ comes, it gives us both the formal relief of the sentence’s finish, while also conveying the open-ended sense of death as a journey into the blackness of the unknown. And it, too, has the liturgical rhythms of a religious prayer.

In the next section of the poem, the imperative mood opens with another command: ‘Reach me a gentian…’ However, this passive, almost surrendering tone gives way to ‘let me guide myself with this blue.’ Here we have the exact reliance on ‘Inner Light’ and primitive, individualist spirituality that Eliot saw as so dangerous. But here, however, it is a lonely religiosity that is all the more courageous for its individualism. Even Persephone here is ‘but a voice/or a darkness invisible enfolded in the deeper dark/of the arms Plutonic…’ The sprawling lines and the sparse punctuation give the verse a breathless, cascading quality, making us feel like we have been hooked and dragged into that darkness. The courage of Lawrence’s lyricism here lies in his unflinching account of its beauty. It is a dark that is so bleak and deep that is seems to glow. The petals of the genital emanate a light in their very dark blueness, and it is this paradox that captures the promise of death. For Lawrence, the underworld of Pluto and Persephone is a place ‘passion’ and ‘splendour’, a place ‘where darkness is awake upon the dark.’

In the final lines the paradoxical language becomes more intense, more mischievously baffling. There is a music created out of the loose approximation of a definite rhythm, using the metrical feet of a spondee (two stressed syllables in a row) and anapest (two unstressed syllables, followed by on stressed). These are not necessarily conscious on Lawrence’s part, and they are not exact. But that is the effect, and it shows that what the poet is doing here is not random gesticulation. He writes that Persephone is ‘pierced with the passion of dense/gloom/among the splendour of torches of darkness, shedding darkness/on the lost bride and the groom.’ This is a couplet, rhyming gloom and groom, and the image of the ‘lost bride’ gives it a gothic quality, a spooky Dickensian chill. Also the verbs are incongruous. How can anyone be ‘pierced’ with gloom, or how can darkness be in any way ‘shed’? But the incongruity helps to affirm Lawrence’s point that the gentians are torches that embody the darkness of death, precisely because they have a strange, ineffable glow.

Lawrence’s figure of the gentians as characterising the mystery of death is a bold one, and this paradoxical truth is aided by his organic, psalm-like rhythm which give his meditations the character of a religious ode. However, this poem is also an affirmation of poetry itself. Lawrence has successfully accomplished the impossible—he has given tangible form to the most terrifying mystery in human life, namely its annihilation. The inscrutable shine of the gentians make them the perfect metaphor for what is otherwise beyond our grasp. And Lawrence’s reaching, sprawling lines, and his recurrent variations on repeated words, help to make this a memorable triumph of aesthetic power.

Eliot saw Lawrence the man as the embodiment of everything that is wrong with modern creativity. It is dependent, Eliot thought, on nothing more than the authentic expression of personality, rather than any objective standard of value, or any stable technique and tradition. Of course, this is based on a silly, false antithesis—one that all rigour-fetishists tend to buy into. Just because we seek authentic and uniquely personal expressions of experience, doesn’t mean that ‘anything goes’ or that the success of a poem lies in the demagogic draw of the poet. Lawrence has proven that a genuine artistic statement in the modern world has to invent its own form as it goes, and that the test is not some external hierarchy, but whether or not it has communicated a beautiful statement that could not be made in any other way.

Bavarian Gentians by D.H. Lawrence

Not every man has gentians in his house

in Soft September, at slow, Sad Michaelmas.

Bavarian gentians, big and dark, only dark

darkening the daytime torch-like with the smoking blueness of Pluto's

gloom,

ribbed and torch-like, with their blaze of darkness spread blue

down flattening into points, flattened under the sweep of white day

torch-flower of the blue-smoking darkness, Pluto's dark-blue daze,

black lamps from the halls of Dis, burning dark blue,

giving off darkness, blue darkness, as Demeter's pale lamps give off

light,

lead me then, lead me the way.

Reach me a gentian, give me a torch

let me guide myself with the blue, forked torch of this flower

down the darker and darker stairs, where blue is darkened on blueness.

even where Persephone goes, just now, from the frosted September

to the sightless realm where darkness was awake upon the dark

and Persephone herself is but a voice

or a darkness invisible enfolded in the deeper dark

of the arms Plutonic, and pierced with the passion of dense gloom,

among the splendour of torches of darkness, shedding darkness on the

lost bride and groom.